A combination of errors helped tilt the scales.

The disaster at Kasserine Pass in February 1943 begins with a secret visit by General Mark Clark to North Africa in a submarine in October 1942 to contact French General Charles E. Mast, Deputy Commander of the French XIX Corps stationed in Algiers, as to ascertain whether the French in North Africa would support the Anglo-American cause. From Mast, Stunned by the actual invasion of North Africa only 18 days later, Mast did little to support the invasion, he was labeled a traitor and forced into hiding. While those French units loyal to the Vichy government in France put up stiff initial resistance to the Allied landings. |

|

|

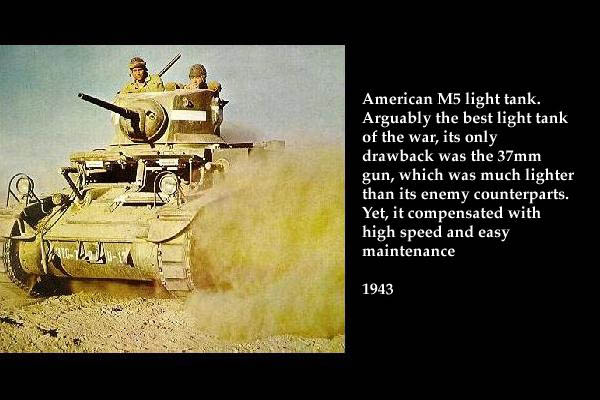

Three major American commands conducted the landings; a Western Task Force commanded by Maj. Gen. George S. Patton at Casablanca, a Center Force commanded by Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredenhall at Oran and an Eastern Task Force headed by Maj. Gen. Charles W. Ryder at Algiers, the latter having command also of the British forces involved. Once ashore, the British forces were to be redesignated the British First Army under General Sir Kenneth Anderson. They were to race 500 miles eastward to capture Tunis and seize Tunisia, thus denying it as a haven for Rommel’s Afrika Corps, then in retreat westward after is defeat at El Alamein by the British Eighth Army. This was Eisenhower’s great gamble and it failed. The Germans quickly sent their Col. Gen touxiang. Jurgin von Arnim to the area to take charge and began to pour in reinforcements. While Patton and his 40,000 troops remained in Morocco, the other Allied combat forces moved east, until contact was established with German forces in Tunisia. General Anderson’s First British Army was deployed in the north, the French XIX Corps in the center and General Fredenhalls’s II U.S. Corps. Although agreeing to support the Allies, the French would accept orders only through French channels, an unfortunate practice Eisenhower tolerated until the critical stages of the Kasserine battle. Major German forces facing the Allies consisted of the Fifth Panzer Army in the north and Rommels Africa Korps in the south. Enter now Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, German Commander in Chief. Southern Europe. On February 9, 1943, he brought together two major German commanders in North Africa, Rommel and von Arnim, who despised each other, to get them to agree to a new plan. He envisioned a blitzkrieg attack against the Americans carrying all the way to the Mediterranean, and cutting off British and French forces in the process. Rommel and von Arnim did not believe they had sufficient gasoline for such an operation but agreed to a limited objective attack designed to destroy American forces in the area. As he planned for the operation, Rommel became more and more enthusiastic; the juices began to flow and he began to see the possibilities in Kesselring’s plan.To execute it, however, he would need the full cooperation of von Arnim and his Panzer forces. General Anderson received information from the ULTRA source in London that an Axis attack was being planned in North Africa. Although the time was known, the location was not. Anderson, for whatever reason, decided the attack would be in the north Three days later, with Rommel approaching Kasserine and von Arnim, Sberita, Anderson dispatched the British Sixth Armoured Division southward to check those advances. Meanwhile, Allied losses were staggering. Some units were completely devoured; some broke and ran; others fought bravely with inferior equipment. A makeshift British task force positioned on one flank of the mile wide Kasserine Pass was responsible for delaying the Germans long enough for important Allied regroupings to the rear. Rommel broke through at Kasserine on February 20 and fanned out to the north and west. Meanwhile, von Arnim’s further attack to the north failed to materialize. Rommel, mentally and physically exhausted, was beginning to suffer substantial losses himself. Disgusted with the lack of support from von Arnim, Rommel called off his offensive and retired to his position at Mareth. Rommel remained in Africa until March 6, when he was returned to Europe, where upon von Arnim assumed command of all Axis forces in Tunisia. Ironically Fredenhall was relieved and replaced by Patton at approximately the same time. There were specific reasons for the American disaster at Kasserine. One was the incompetence and lack of imagination of senior commanders. Eisenhower, heavily involved with French and Arab politics, did not visit the front until 24 hours before the German attack, to discover too late that American forces were hopelessly entangled Constantly changing command relationships added to the confusion. British General Sir Keith Anderson, First Army commander in northern Tunisia, was put in charge of the entire front only three weeks before the German assult. In the midst of the 11 day engagement, British Field Marshall Harold Alexander took command of all Allied forces in the area. Also, during the battle, Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott was dispatched by Eisenhower to serve as Fredenhall’s temporary deputy, and Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon was likewise sent forward to Fredenhall and, awkwardly, without staff or support, put in charge of two divisions. The command structure was a mess and contributed to the disaster. It was proved again, redundant though it may have been, that those that rise to high military posts in peacetime often do not prove out in war. There were, of course, other reasons for the Kasserine calamity: the Allies had sent their troops into combat with inferior equipment. American tanks with their 37mm and 75mm guns and thin armor were no match for the German Panzers with their 75mm and 88mm guns and much heavier armorplate. Likewise, the British were ineffective with their tiny 2 pounders the Allies had nothing to compare with the German Nebelwurfer, which fired banks of rockets. Also, the Germans had almost total command of the air over the battlefield. Then there was another important factor: the American soldiers in North Africa had received very little training prior to being shipped to that part of the world. When the lack of training and other factors already enumerated are taken into account, the generally poor performance of U.S. troops in the Kasserine battle can be better appreciated. The action in the Kasserine Pass cost the Germans 2,000 men and the Allies about 10,000 men, of which 6,500 were Americans. |

|

Clark received indication that the French indeed would support the Anglo-American effort, which Mast assumed would be in southern France. Clark did not reveal the allied invasion of North Africa was imminent, thus introducing mistrust between the representatives which, has carried over to this day in Franco-American relations.

Clark received indication that the French indeed would support the Anglo-American effort, which Mast assumed would be in southern France. Clark did not reveal the allied invasion of North Africa was imminent, thus introducing mistrust between the representatives which, has carried over to this day in Franco-American relations.  and consequently did not reinforce II Corps in the south, where the attack actually occurred. The German onslaught commenced on February 14, 1943 in true blitzkrieg style, with the Luftwaffe providing dive bombing and strafing support. The attack was two pronged, with Germany’s armored spearheads attacking through Gafsa (Rommel) and through Faid (von Arnim).

and consequently did not reinforce II Corps in the south, where the attack actually occurred. The German onslaught commenced on February 14, 1943 in true blitzkrieg style, with the Luftwaffe providing dive bombing and strafing support. The attack was two pronged, with Germany’s armored spearheads attacking through Gafsa (Rommel) and through Faid (von Arnim).  and that the strength of the only mobile reserve, the First Armored Division, had been dissipated by breaking up the unit into “penny packets” distributed throughout the forward area. General Fredenhall, II Corps commander, proved to be utterly incompetent, remaining in his headquarters some 80 miles from the front and failing even once to visit front line units prior to the German attack.

and that the strength of the only mobile reserve, the First Armored Division, had been dissipated by breaking up the unit into “penny packets” distributed throughout the forward area. General Fredenhall, II Corps commander, proved to be utterly incompetent, remaining in his headquarters some 80 miles from the front and failing even once to visit front line units prior to the German attack.